The 'Bridgerton' Fandom and I

A Brief(ish) Study in Adapting Romance, Romanticizing History, and How People Feel About That

My interest in Bridgerton has almost always been mostly academic. I have never really felt any personal emotional connections with any of the characters (though I have enjoyed many of the actors’ performances), and I don’t have any attachment to the source material. I’ve also never held any solid opinions about whether the show, whether as an adaptation or as a standalone work, is “good” or “bad,” or even really whether I like it or not. (I suppose I like it well enough to keep watching, so we can leave it at that.) But in general I don’t find discussions that begin and end with whether something is simply good or bad interesting.

What does interest me about Bridgerton are the ideas it explores and represents. I’m fascinated by the concept of adaptation theory, and how the show is choosing to adapt its source material, which is a series of romance novels. I’m also intrigued by how Bridgerton builds a fantasy world that is inspired by history, but is clearly not literally meant to be historically based. And a third meta aspect of the show that I’m increasingly realizing holds a certain interest for me is how its fandom interprets and discusses the series.

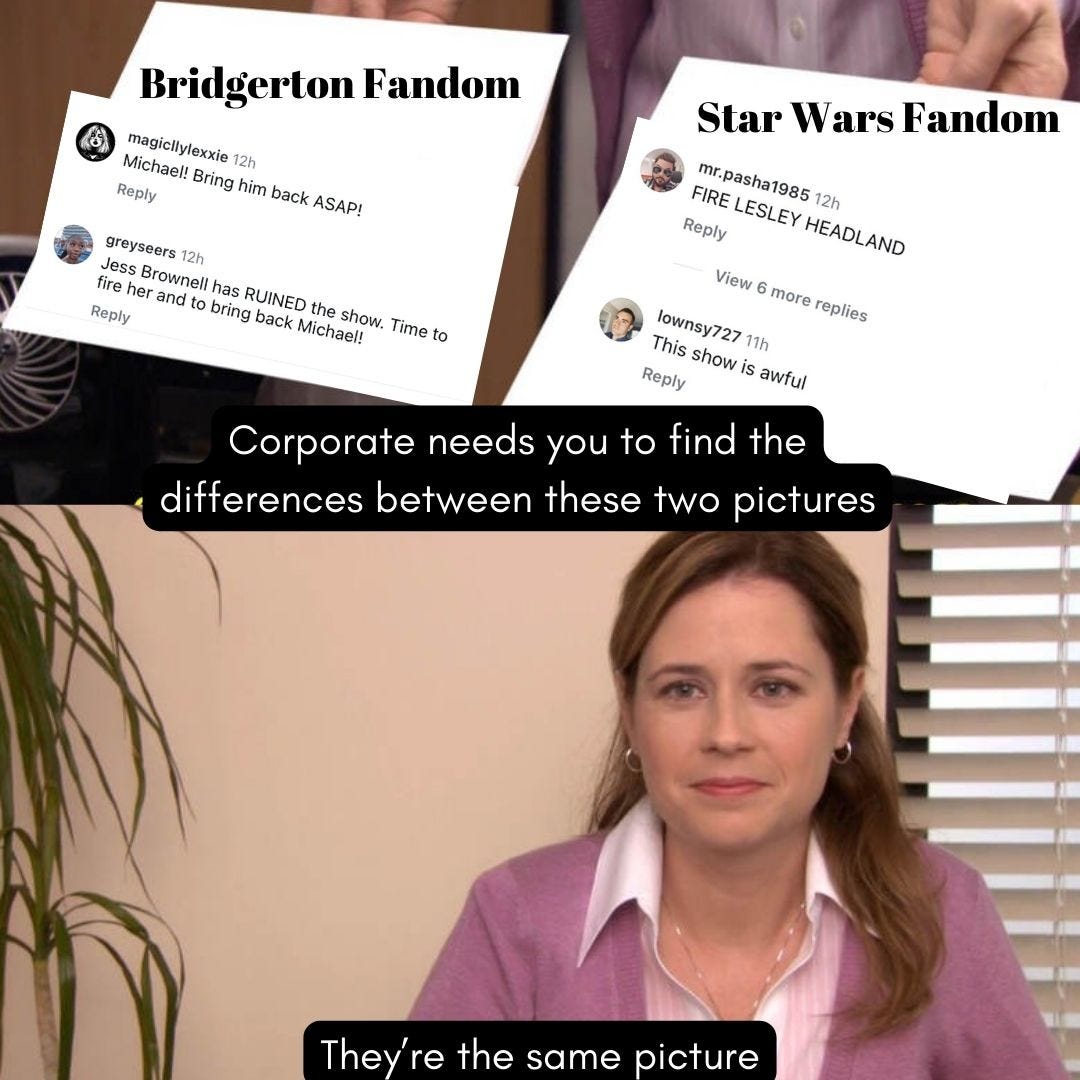

The timing of the release of Part 2 of Season 3 has been especially illuminating as it coincided closely with the premiere of the latest Star Wars TV series, The Acolyte, which has had more than its fair share of negative fan reaction. As I’ve observed fan discussions surrounding both The Acolyte and Bridgerton across social media platforms, I’ve seen some notable parallels between the language used and general tenor of sentiment toward these two series that are aesthetically very different, and though there is undoubtedly overlap in fandom and viewership (I am proof), are nevertheless targeted toward different audiences.

I don’t think these parallels are irrelevant to this discussion I’d like to have, but I’ll get to that a bit later. For now, let’s look at how Bridgerton has approached adapting its source material.

“Bridgerton is Bad Because it Changed the Books”: Adaptation Theory and You

In a widely-reported May 24th blog post, George R. R. Martin gave a rather “old man yells at cloud” take on literary adaptations for the screen, writing:

Everywhere you look, there are more screenwriters and producers eager to take great stories and “make them their own.” It does not seem to matter whether the source material was written by Stan Lee, Charles Dickens, Ian Fleming, Roald Dahl, Ursula K. Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, Mark Twain, Raymond Chandler, Jane Austen, or… well, anyone. No matter how major a writer it is, no matter how great the book, there always seems to be someone on hand who thinks he can do better, eager to take the story and “improve” on it. “The book is the book, the film is the film,” they will tell you, as if they were saying something profound. Then they make the story their own.

He doesn’t name Julia Quinn in his list of “major” authors whose works should apparently never be interpreted as anything other than their literal on-page contents, but I have observed enough to know that many Bridgerton fans would agree with this sentiment to some degree. From the moment the series was announced and it was revealed that several actors of color had been cast as characters who are white in the books, there was an outcry about both “historical accuracy” and how the show was “changing the books.” There was a similar lament of the series’ lack of “accuracy” to the book when Season 2 made several major changes to the plot of the second novel. And with the most recent season ending with a reveal that a love interest character from one of the books has been gender-swapped, there has been further negative discourse.

I can understand to some degree a feeling of disappointment from fans who have stronger associations with the books at certain aspects of them being changed (unless they’re disappointed about the inclusive casting, because that’s just racism). But I can not agree with an approach to adaptation in which the adapters and filmmakers are NOT, as George R. R. Martin so deridingly phrases it, trying to make the book their own. If you don’t feel a sense of ownership in a way over a literary work, if you don’t have a personal connection to it and a unique interpretation of it that you want to share with the world, in other words, if you’re NOT going to “make it your own,” why would you even be interested in adapting it at all?

Shonda Rhimes sought out the adaptation rights for the Bridgerton series of books because when she read them she saw something that sparked her interest, that made her think, and that made her want to say something about them. As The Hollywood Reporter noted in 2020:

“I remember I was almost scaring people, like, ‘We have to get these crazy romance novels — they’re hot and they’re sexy and they’re really interesting,'” says Rhimes. That the multi-book collection from author Julia Quinn had an expansive web of characters and entry points as well as a fervent international fanbase made Rhimes that much more confident in its streaming potential.

Rhimes’ excitement for the source material is exactly what I personally want to see in someone choosing to adapt a literary work. She has a clear point of view on the books, and it’s one that many readers might not agree with, but that’s what makes it interesting. Though she handed the show off to her longtime collaborator Chris Van Dusen to executive produce for the first two seasons, there are still clear hallmarks of Rhimes’ previous work in Bridgerton, elements that perhaps make the series less “faithful” to the books. You might even say she made them her own.

If our measure of an adaptation’s quality or legitimacy begins and ends with its fidelity to its source material, we are tragically and completely missing the point of adaptation. Linda Hutcheon’s seminal 2006 work A Theory of Adaptation rejects the notion of “fidelity” to source material as a metric by which to discuss adaptations. Hutcheon posits that adhering to faithfulness to source material as a measure of quality creates a false hierarchy, placing the original or source work above its adaptation in importance or validity, and undermining the adaptation’s value as a work of art in its own right. A 2000 essay by Robert Stam, “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation,” makes a similar assertion:

The demand for fidelity ignores the actual process of making films–for example, the differences in cost and in modes of production.

Most novels are far too long to translate every single scene and line of dialogue and minute detail onto the screen without producing a 15- or 20-hour work, or longer (although, I think that is what some people actually want). That would be prohibitively expensive in many cases, not to mention probably pretty tedious, and would completely rule out the precise and dynamic art form of the feature-length film. Another problem with the idea of fidelity in adaptation is what exactly the adaptation should be faithful TO, as Stam goes on to elaborate:

The question of fidelity ignores the wider question: fidelity to what? Is the filmmaker to be faithful to the plot in its every detail? … Or is one to be faithful to the author’s intentions? But what might they be, and how are they to be inferred? Authors often mask their intentions for personal or psychoanalytic reasons or for external or censorious ones. An author’s expressed intentions are not necessarily relevant, since literary critics warn us away from the “intentional fallacy,” urging us to “trust the tale, not the teller.”

In the specific case of Bridgerton, the authorial intent point is interesting, as Julia Quinn has publicly given her approval of the series on several occasions. Talking to Entertainment Weekly in 2020 right before the premiere of the first season, Quinn said:

They've brilliantly adapted The Duke and I, but also they brought these other side characters to life to make it more than just the one book, and to lay down little pieces to hopefully lay the framework for future seasons… In terms of the stories and the emotions of the characters, everything has been spot on.

Just last month (as of this writing), Quinn told People Magazine:

Obviously it's the romance, and Nicola [Coughlan] and Luke [Newton] [who play the third season’s romantic leads] are amazing, but it's such an ensemble cast and there's so many little moments with everyone, which I think are just so fabulous.

Quinn’s point about the show featuring an ensemble cast is crucial to the discussion of how the series has been adapting the books. A romance novel, even a romance novel in a series, is fundamentally different from a season of a romantic drama TV show, both in form and function. In traditionally published romance, typically each book within a series is essentially a standalone story. They are usually connected through a group of friends or siblings (as in the Bridgerton books), each of whom gets their own installment that features their romance. There may be arcs for minor side characters across multiple books, but in general, readers won’t need to read them in a particular order to be able to understand one of the books on its own.

Such is not the case for most TV dramas. With the Bridgerton show as a prime example, in an ensemble TV drama, the arcs of main characters develop significantly from season to season. There are much stronger connective ties between installments than with the typical romance book series. As Stam notes, in order to fit the constraints or conventions of an adaptive form (such as film or TV), changes or ADAPTATIONS must often be made to a source text, whether in terms of plot revisions or condensing, or character adjustments, or any other number of changes to serve the adapter’s vision and interpretation of the text.

In the case of Bridgerton, I don’t have an interest in defending any particular choices that were made in its adaptation. I can respect viewers not liking or disagreeing with certain choices, but I doubt any of those changes were made without reason. In general, I also personally think some of its changes are improvements upon the source material, and almost all of them serve a purpose in adapting the story to its new art form.

(I don’t want it to sound like I’m a Bridgerton apologist here. I actually didn’t enjoy Season 3 quite as much as the first two seasons, but not because of its adaptational changes. But that’s a discussion for another time.)

“Bridgerton is Bad Because it’s Not Historically Accurate”: The Fantasy of Historical Romance

Historical romance can, and perhaps should, be read not as historical fiction, but as a form of speculative fiction, even fantasy. In fact, let’s look at the relationship between high fantasy and historical romance. Both are going to give you an aesthetically pre-modern world, likely with antiquated social customs and norms. There will probably be horses and carriages, maybe some sword fights, maybe some gowns. Both genres are much more likely to have clear-cut villains than, say, a contemporary romance, and to have characters who are of the royal or noble classes. And crucially, both are going to give readers an escape into a world that looks very different from ours.

The only significant world-building differences between these two genres are that in (most) historical romance there’s no magic, and the setting is more directly tied to a historical time and place in our world. A Regency Romance like the Bridgerton books, for example, is going to be set in England sometime between 1811 and 1820. But in historical romance in general, and I would say Regency Romance in particular, that setting is still less tied to the actual historical time period, and more to a version of Regency England that only exists in Regency Romance.

The inside joke among historical romance readers is that England must be sinking under the weight of the tens of thousands of dukes, earls, and other titled nobles that have been created by romance authors. Regency Romance in particular has such a strong genre identity that familiar plot devices, character archetypes, and settings are constantly being reintroduced in new entries in the genre in unique ways. I created this Regency Romance BINGO card when discussing Sophie Irwin’s A Lady’s Guide to Fortune Hunting for a book club; Bridgerton checks off most of these boxes, too:

With all of this in mind, the setting of a Regency Romance is almost as much a product of the author and readers’ imaginations as a high fantasy setting would be. The Bridgerton TV series makes this fantastical setting more overt than most romance books, dropping its first hints in Season 1 that the world of the show is not rooted in the real history of our world, but in an imagined alternate history. The spinoff series Queen Charlotte elaborates on this concept further with a disclaimer at the opening of its first episode reading:

Dearest Gentle Reader: This is the story of Queen Charlotte from Bridgerton. It is not a history lesson. It is fiction inspired by fact. All liberties taken by the author are quite intentional.

In other words, “we’re not trying to be historically accurate, so you have no reason to complain.” And yet, there are people still talking about Bridgerton and historical accuracy in the same sentence in 2024. Analyzing the historical accuracy of the costumes and hair, of the dialog, social customs, and world events in a work that is not historical, but is in fact fantasy, is a pointless exercise. I mean, I guess if you enjoy that, good for you. But judging Bridgerton, or any show, by criteria it does not claim or even attempt to fulfill is the very definition of bad faith criticism.

As much as “book accuracy” and “historical accuracy” are (in my opinion) irrelevant standards to which to hold media works, at least they are understandable preferences with communicable objectives. But there are also criticisms I’ve observed being made of Bridgerton in particular, among other current works, that have no such justification other than personal preference, which is valid. But it turns into bad faith criticism when the critic takes for granted that their personal preferences are objective standards.

“Bridgerton is Bad Because I Don’t Like It”: No One Hates Star Wars More than Star Wars Fans

Among the many wise adages I picked up from my late grandfather is one that he often repeated in reference to foods I didn’t like as a child (I was a picky eater): “It’s good if you like it.” Though he was referring to foods, I think we can apply this simple yet brilliant logic to anything about which people can have subjective opinions, including and especially art and media works such as books, films, and television shows.

There is no such thing as objectively good or objectively bad art. We can certainly measure works of art by established standards—things like the three-act structure in film, the rule of thirds in visual art, or preferred styles of prose in fiction. But all of these “rules,” even though they are agreed upon by large groups of people, are still subjective. Art isn’t “wrong” or “bad” if it doesn’t follow established rules; it’s just different. You’re not wrong for liking something that goes against the “rules.” It’s good if you like it.

Conflating personal preference with objective quality in art and media criticism isn’t by any means new, as most fans of big, popular media franchises can no doubt attest to. Especially in long-running and prolific bodies of work, eventually individual works within the franchise will be produced that many fans will claim are in some way “untrue” to the originating works that the franchise expands upon. In a way, such critiques can be applied to Stam’s exploration of the language of adaptation discussion:

The language… has often been profoundly moralistic, awash in terms such as infidelity, betrayal, deformation, violation, vulgarization, and desecration, each accusation carrying its specific charge of outraged negativity.

In such cases that I am thinking of, those exact terms haven’t necessarily been used, but rather phrases such as “you’re ruining my childhood” or “this is sh*tting on [original work’s creator]’s legacy” or “bring back this beloved character” or “fire the showrunner.” I believe no fandom exemplifies this attitude and tenor of social media comments more than the Star Wars fandom, but recently the Bridgerton fandom is giving it a run for its money.

Let’s play a game. I’ll give you a few recent comments I’ve seen on Instagram, and you try to guess if the comment was on a post from the Star Wars account or the Bridgerton account. Ready?

Maybe address your upset fans considering we fund the show. Disgraceful.

You ruined [franchise]

What did [creator of original work] do to deserve this?

We don’t want [showrunner]’s fanfiction. Fire them!

“Surely posting more about the show will make people like it more!” [laughing face emoji]

The person running the account: if we just keep posting, they will eventually stop commenting [negatively]

(Answers: 1, 4, & 6: Bridgerton; 2, 3, & 5: Star Wars)

If you got all of them right there’s no prize, sorry. There’s also really no way to effectively counteract this kind of toxic fandom attitude. People are going to have their opinions, which they have a right to, and express them however they want, which they also have a right to as long as they’re not harming anyone. Even when this toxicity actually does harm people—with numerous actors from the Star Wars franchise actually being bullied off of social media, and now the toxic segment of the Bridgerton fandom starting to flood actors’ accounts with negative comments about the show—there’s not a lot that not-toxic fans can really do that will significantly mitigate this harm.

But you know who can do something that will have an impact? The studios and production companies that make these works. Lucasfilm has released statements in the past when the fandom’s misogynoir against an actor reached an especially horrific height that I won’t even link a reference to because it’s so upsetting. But there is no doubt so much more that these powerful companies—Disney and Netflix dominate the entertainment industry and the world economy in unprecedented ways, they have the power and influence—could be doing than just constantly posting and feigning ignorance, as both currently seem to be doing.

“Bridgerton is Bad Because… I Don’t Know, I’m Just Tired of Popular Franchises Fumbling So Hard”: Where Do We Go From Here?

The problems that I personally had with Season 3 of Bridgerton, and I think most of the problems I tend to see with current media works in general as of late, are at their roots about issues that are much bigger than any individual work. The prioritization of profits over people, and over artistic integrity, and unchecked economic growth, mergers, and monopolies benefit no one but the few people at the very tops of these industry giants.

And I think that for many fans of popular works, at least some of the dissatisfaction being expressed is related to those issues. Not all of it, because of course some people are just terrible and will be toxic and bigoted regardless. But if there’s one thing George R. R. Martin and I can agree on, it’s that stories worth telling take time. So in a world where time is money, and money is the goal, the storytelling will be what suffers.

I don’t have any answers. I’m just as tired as you. And I don’t believe in false positivity that ignores real problems. If there’s any hope to be found in the current media landscape it’s that there are still artists making great things, and there are still great people enjoying them and discussing them. I hope I get to continue seeing cool stuff. I hope you do too.

I like the thought of letting an adaptation stand on its own merit as a piece of art...however it differs or relates to it's source.

I was just thinking about different adaptations of Cinderella. The two I'm thinking of were written to appeal to certain mindsets in the time it was produced. In the 1997 Cinderella the cast was multicultural- this was a new concept for the time. It was controversial for the time- I found it refreshing! In Ever After (1998) the character of Cinderella is written and acted as a very strong and independent woman. She doesn't "need" a man but her life and the prince's are enhanced by being part of each other's.